CMU's Iris Lunar Rover Meets Milestone for Flight Student-Designed Robot Will Land on the Moon in 2021

Byron SpiceTuesday, May 12, 2020Print this page.

Carnegie Mellon University students who designed and built a small, boxy robot, called Iris, have achieved a major milestone: their robot passed its critical design review by NASA and is on track to land on the moon in the fall of 2021.

"We are moving forward … we're going to the moon," a triumphant project manager, Raewyn Duvall, told Iris team members during a Zoom meeting following the review.

Officials at NASA and Astrobotic Inc., whose Peregrine lander will deliver the robot to the lunar surface, performed the review. Duvall, a Ph.D. student in the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, said the process resulted in a few small design revisions, which the team is now incorporating.

The team will replace prototype parts with flight components this summer, as they test the robot to prove that it can withstand the trip to the moon without causing problems for Peregrine or other payloads aboard the lunar lander.

"This is going to be an exciting summer," said William "Red" Whittaker, professor in the Robotics Institute and director of the Field Robotics Center.

Once the robot passes the payload acceptance review this fall, the team will deliver the fully flight-ready Iris to the company by the end of the year so it can be integrated with Peregrine.

"The vision, design and implementation for this robot are driven by amazing student power — unprecedented for a space venture of this ambition and technical challenge," Whittaker said. "It requires the highest standards of commitment, collaboration and cross-disciplinary skill, as well as incredible resourcefulness."

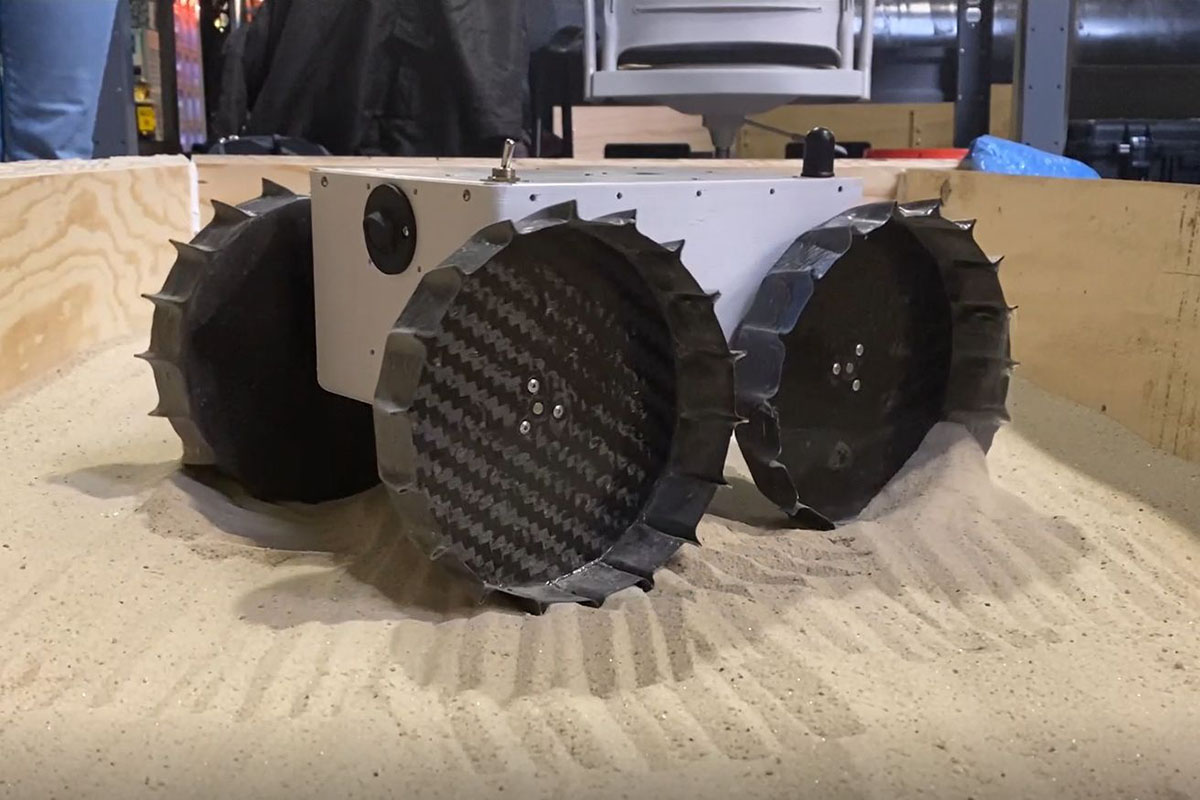

The four-wheeled Iris, which weighs about four pounds, will be America's first robotic rover to explore the moon's surface. Although NASA landed the first humans on the moon and has explored Mars with rovers, it has yet to launch a lunar rover. Russia and China have both operated unmanned rovers on the moon.

Last year, NASA awarded a contract to Pittsburgh's Astrobotic to deliver 14 scientific payloads to the vicinity of Lacus Mortis, or Lake of Death, a large pit the size of Pittsburgh's Heinz Field. In a separate agreement with CMU, Astrobotic has agreed to deliver Iris and a CMU arts package called MoonArk on that mission.

Whittaker and his students began developing the robot in 2017, with support from NASA. They envision it as the prototype for a new family of affordable robots that might be used by small research groups without the resources of a space agency. Astrobotic plans to offer these "CubeRovers" as a product line.

CMU's robot was recently named Iris, in part to honor Siri Maley, a former master's student in mechanical engineering who was a leader and an early champion of the robot's development (Iris is Siri spelled backwards). Also, the robot's main sensors are two video cameras and, in cameras, an iris is a diaphragm that controls the amount of light that enters the lens. Finally, Duvall noted, an iris is a flower known for withstanding extreme environments, just as the robot will on the moon.

Duvall said usually about 40 students — primarily undergraduates — were involved each semester, though the ranks swelled to more than 70 this semester.

"The fact that it's going into space has been a strong pull for student involvement," she explained.

As a student project, the robot went through many design changes, in part because each succeeding group was eager to put their own twist on it, Duvall said. But building a light robot also required some difficult design choices.

One major change was the number of wheels. Iris began as a two-wheeled robot supported in the rear by a tail that dragged along the surface. The idea was that the lightweight tail replaced heavier wheels. But the tail caused so much drag that the team decided to add two wheels, foregoing the weight advantage in favor of saving energy, Duvall said.

Nick Acuna, a sophomore mechanical engineering major, joined the project as a first-year student, though he doubted he could contribute much that was useful. Assigned to the wheel design group, he discovered a way to make carbon composite wheels that "worked really, really well." It enabled the wheels, which resemble bottle caps, to be both lighter and stiffer. By the end of last summer, he had been elevated to mechanical lead.

"This project is pretty important to me," Acuna said, explaining that he enjoys going "all in," focusing his drive on a single thing. In high school, wrestling was his focus. Now, with Iris, "I've slowly gotten to that same mindset." Working on CMU's first space program is nothing short of inspiring, but also humbling, he added.

"It lets you dream about what you can accomplish in the future, if you're already doing this as a student," he explained. "I know a lot of great people have come through this project. We have the privilege of being the team in the semester when we bring it all to fruition.

"All these giants have touched it and we're the ones who get to see it through to the end."

Byron Spice | 412-268-9068 | bspice@cs.cmu.edu<br>Virginia Alvino Young | 412-268-8356 | vay@cmu.edu